I am on my way to Cape Town for a holiday and to work on my script that will go into production in April 2013, so I will not be posting until January. Happy holidays!

Chris

Thursday, November 22, 2012

Monday, November 12, 2012

Art & The Market: A History

A seriously interesting article on the relationship between art and the market is in "Believer" magazine. Here is a quote from the article by Rachel Cohen:

For as long as artists have made a living from their art, even if a meager one, some version of the art market has been negotiated between people with power and people with artistic talents. But in each era, what was held to be valuable was different. Though the art market has always measured value, that value was not always expressed in exclusively financial terms. Take, for example, fifteenth-century Florence, where the Medici banking family held sway. At that time, bankers worked in long-term partnerships with one another, and painters had workshops that were passed down from master to apprentice. Ongoing relationships with men of standing were very valuable. The exchange between, say, Lorenzo the Magnificent and Botticelli took the form of an enduring patronage relationship with large-scale commissions for churches and palazzi. Much of the value exchanged was not monetary but religious or reputational. Both the banker and the painter were understood to be more pious and significant men as a result of their relationship.

But in the Gilded Age, price was increasingly felt to be the measure of value which subsumed all others.

In 1825, a Botticelli of the Holy Family sold for £10 and 13 shillings. In 1898, when offered another well-known Botticelli, of Saint Jerome, for £500, the British National Gallery was content to turn it down. But in 1912 that Saint Jerome sold to the American collector B. Altman for about $50,000. And by the time Andrew Mellon, in 1931, bought a Botticelli, together with a Rembrandt, he felt he was getting a rapaciously good bargain at a mere $1 million. Works by Botticelli were becoming increasingly prized during this period, but prices for all of the most valued paintings leaped up almost shockingly in the years before and after the first IPOs and the first cubist pictures. Suddenly people began to see paintings as representations not only of age-old values but of future values. And once they began to look at them that way, it mattered less how much time they’d withstood the test of. What people became interested in was not what the pieces were worth a hundred years ago but what they might be worth tomorrow. All through the twentieth century, prices for contemporary artwork were rapidly catching up to prices for works by old masters. Now, the first time a Damien Hirst is sold, the price is at a level only the greatest works of the past have achieved after being sold and resold for a century or more.

Here is the link to the whole article.

Monday, October 22, 2012

What prehistoric art tells us about the evolution of the human brain.

Everyone answers the question “What makes humans human?” in her own way, but if you were ever a liberal arts student, you might have to resist the urge to roll your eyes and reply, “The humanities.” Maybe you’d get more specific, quoting the critic Haldane McFall: "That man who is without the arts is little above the beasts of the field."

OK, so you’d be pretty pretentious, but would you be wrong? Not really. Paleontologists tend to link the development of modern human cognition to the rise of our ability to express ourselves as artists and historians through cave painting, sculptures, and other prehistoric art. Representing the world in symbols may have heralded the beginnings of language. Creating paint from charcoal, iron-rich ochre, crumbled animal bones, and urine meant understanding how materials could combine to form substances with new properties. Storing the paint—perhaps in an abalone shell that would be discovered 100,000 years later in a cavern on the South African coast—required innovation and planning ahead.

Link to whole article on Slate.

Link to whole article on Slate.

Tuesday, October 2, 2012

Pledging

“Pledge.” When was

the last time you heard that word? It’s an old word it seems, one you rarely

hear any more. A “Pledge” was a freshman applicant to a fraternity or sorority when

I was in college. Otherwise, the only other times I heard the word were was in

the phrase, “Pledge of Allegiance” or when the housekeeper wanted me to get

some (Pledge) furniture polish.

The word has a long history and diverse applications, but most of us understand it to mean “a promise to do, or not to do something.” When someone says to you, for example, ”I promise to take the garbage out in the morning,” that is a pledge. Pledges are a big part of addiction recovery programs

Simple pledges between friends function as informal oral contracts. In the loan, mortgage bail and pawn industries, written commitments guaranteeing repayment and itemizing collateral are formal legal pledges of repayment and security. But perhaps the most pervasive use of a pledge in our society is the oral vow made at weddings.

The most important element of wedding and addiction recovery pledges are the witnesses. We recognize the challenges involved with the nature of their pledges can be significant, so the public nature of these pledges—presence of witnesses—is strategic. A wedding unites two families that want the marriage to last; marital longevity is good for society and the children of the couple. Consequently, our society has placed witnessed oral vows at the heart of the marriage believing the witnesses and pledges will serve the pledgers well during difficult times.

In addiction recovery communities, the same thing happens. Participants are required to verbalize their commitment to sobriety in order to engage the ongoing support of their peers. Both these applications recognize the power of witnessed public declaration; witnesses provide us with strength and external discipline. I have found, therefore, that making pledges can be a highly effective tool in my professional tool chest.

I made my first pledge to you, Opus readers. You may have missed it, but I wrote a column for this newsletter about five-and-a-half years ago in which I said I was writing a book about professional development for visual artists. When Opus heard about my plan, they ordered a thousand books and suddenly I not only had discipline, I also had a deadline.That book led to a nice modest teaching offer from Emily Carr University, a second book, an exhausting number of invitations to lead workshops and present lectures and a new career. I couldn’t be happier and the experience gave me an idea.

I have long been involved with a charity that provides subsidized housing to veterans of the performing arts industry. We are a bunch of former theatre professionals operating as a charity and like all charities we must constantly fundraise in order to offer the housing subsidies we do. So I started thinking about how I could use a pledge as a fundraiser.

That led, in 2011, to me writing to most of my friends asking them to pledge a sum per kilometer as sponsors of a 1,200 kilometer walk I was planning (the distance from Vancouver to San Francisco). Their pledges would all go to my charity—Performing Arts Lodge Vancouver (PAL Vancouver; www.plavancouver.org). My friends pledged and paid $18,600 and so, when my legs were swollen and sometimes bleeding and I wanted to quit, I kept walking because of the self-imposed pressure of my pledge and my witnesses.

With that project completed, I set a new goal. I worked on it, refined it, abandoned it, came back to it and then I started talking to my closest friends about it to see what they would say. It grew and it changed, and so I have made another pledge to friends that will benefit PAL Vancouver. I pledged to attempt the hardest thing I have ever tired to do (and the last thing on my “bucket list”). It will push me harder than my walk but if it works, I will live the rest of my life with a legacy of tremendous pride and fulfillment. (And I will have raised over $100,000 for PAL Vancouver with my various efforts.)

I am not going to tell you what my new pledge is about—yet. I’ll do that in 2013. I have told you about my pledges to illustrate how effective making public pledges has become for my creative practice. Now, I have all my students at Emily Carr make a career-relevant pledge as one of their assignments. Besides discipline, public pledging has brought energy, ideas, collaborators and other forms of help to my practice.

The last thing I must say about my new career development tool is about pacing. Since adopting this fabulous new way of making pledges, I only do it once every two years. To do it more often would ruin the novelty of them; my pledges have to be unique, compelling and motivational to my witnesses and that can only happen with lots of time in between.

Try it. You’ll like it. It works!

The word has a long history and diverse applications, but most of us understand it to mean “a promise to do, or not to do something.” When someone says to you, for example, ”I promise to take the garbage out in the morning,” that is a pledge. Pledges are a big part of addiction recovery programs

Simple pledges between friends function as informal oral contracts. In the loan, mortgage bail and pawn industries, written commitments guaranteeing repayment and itemizing collateral are formal legal pledges of repayment and security. But perhaps the most pervasive use of a pledge in our society is the oral vow made at weddings.

The most important element of wedding and addiction recovery pledges are the witnesses. We recognize the challenges involved with the nature of their pledges can be significant, so the public nature of these pledges—presence of witnesses—is strategic. A wedding unites two families that want the marriage to last; marital longevity is good for society and the children of the couple. Consequently, our society has placed witnessed oral vows at the heart of the marriage believing the witnesses and pledges will serve the pledgers well during difficult times.

In addiction recovery communities, the same thing happens. Participants are required to verbalize their commitment to sobriety in order to engage the ongoing support of their peers. Both these applications recognize the power of witnessed public declaration; witnesses provide us with strength and external discipline. I have found, therefore, that making pledges can be a highly effective tool in my professional tool chest.

I made my first pledge to you, Opus readers. You may have missed it, but I wrote a column for this newsletter about five-and-a-half years ago in which I said I was writing a book about professional development for visual artists. When Opus heard about my plan, they ordered a thousand books and suddenly I not only had discipline, I also had a deadline.That book led to a nice modest teaching offer from Emily Carr University, a second book, an exhausting number of invitations to lead workshops and present lectures and a new career. I couldn’t be happier and the experience gave me an idea.

I have long been involved with a charity that provides subsidized housing to veterans of the performing arts industry. We are a bunch of former theatre professionals operating as a charity and like all charities we must constantly fundraise in order to offer the housing subsidies we do. So I started thinking about how I could use a pledge as a fundraiser.

That led, in 2011, to me writing to most of my friends asking them to pledge a sum per kilometer as sponsors of a 1,200 kilometer walk I was planning (the distance from Vancouver to San Francisco). Their pledges would all go to my charity—Performing Arts Lodge Vancouver (PAL Vancouver; www.plavancouver.org). My friends pledged and paid $18,600 and so, when my legs were swollen and sometimes bleeding and I wanted to quit, I kept walking because of the self-imposed pressure of my pledge and my witnesses.

With that project completed, I set a new goal. I worked on it, refined it, abandoned it, came back to it and then I started talking to my closest friends about it to see what they would say. It grew and it changed, and so I have made another pledge to friends that will benefit PAL Vancouver. I pledged to attempt the hardest thing I have ever tired to do (and the last thing on my “bucket list”). It will push me harder than my walk but if it works, I will live the rest of my life with a legacy of tremendous pride and fulfillment. (And I will have raised over $100,000 for PAL Vancouver with my various efforts.)

I am not going to tell you what my new pledge is about—yet. I’ll do that in 2013. I have told you about my pledges to illustrate how effective making public pledges has become for my creative practice. Now, I have all my students at Emily Carr make a career-relevant pledge as one of their assignments. Besides discipline, public pledging has brought energy, ideas, collaborators and other forms of help to my practice.

The last thing I must say about my new career development tool is about pacing. Since adopting this fabulous new way of making pledges, I only do it once every two years. To do it more often would ruin the novelty of them; my pledges have to be unique, compelling and motivational to my witnesses and that can only happen with lots of time in between.

Try it. You’ll like it. It works!

Wednesday, September 26, 2012

The Fabulous Robert Genn's Take on the Current Market

The incredibly talented and generous Robert Genn has posted a fabulous article on the current art market.

A lot of this transition is due to the advent of the Internet. Even a few years ago my friends and I were agreeing that folks wouldn't buy art on the Net. How wrong we were. Many of my best dealers now do 40% of their business online. And they're doing it not just locally, but worldwide.

An interesting parallel I would have never thought possible is Yoox. It's an international online fashion clothing operation based in Italy that sells up-market duds (Prada, Armani, Jil Sander, etc). Yep, expensive couturier stuff you have to try on to see if it fits. This company, started in 2000 by Federico Marchetti, is now one of the largest rags retailers in the world. They don't have a store.

Read the full article here.

Labels:

Artrepreneur,

Direct Sales,

Internet Sales,

Sales

Monday, August 20, 2012

What is the key to artistic success?

I began teaching in Continuing

Studies at Emily Carr University shortly after my book, Artist Survival Skills, came out. I had picked up a Continuing

Studies calendar to see if there was a course that I might take and noticed that

the listing for a course called The

Business of Art showed the teacher was TBA (to be announced).

I contacted the University to offer

my services for what I thought would be one semester, assuming the regular

teacher was on leave, but I have taught the course every semester since. I am

only in the classroom for six hours a week for two months each semester, but my

course is a compulsory part of three certificate programs so normally, there

are twenty students in each of my two classes.

My challenge with the class is to

make it relevant to a diverse range of students. Some students have

considerable experience while others have none, and they work in vast range of

media. Some make product swhile others provide services; some are mature and

some are very young; most are female. I would say that the average age is

fourty-ish.

Sometimes the interaction can go in

surprising directions. In the recent past, one of my students was very

confrontational in class and submitted illiterate assignments. When I asked for

an appointment to discuss how we could work together to make sure that the

student did not fail, I was refused so I asked my supervisors for advice.

That led to a meeting between my

supervisors and the student and that, in turn, led to the R.C.M.P. calling me

to ask if I had ever discussed guns, owned a gun, referenced Columbine or

student-slaughters or if I had threatened the student. It was the most shocking

and unexpected outcome imaginable even though the University had advised me the

call was coming and not to worry. That student was removed from the class and

our class was relocated for the duration of the term.

The more common experience, however,

is overwhelmingly positive. Every term there students who make it exciting for

me to go to every class. This summer, however, was outstanding. Amongst the

registrants were two

students (a couple) from Switzerland who were inspiring, three delightful

lawyers, a highly energetic and thoroughly engaging and hard-working University

administrator and an equally appealing financial industry executive, a

frustrated engineer/entrepreneur and several international students possessed

of an incredible work ethic and many others—too many to mention here.

The

high percentage of professionals in my class is yet another outcome of the baby

boom. The front edge of the boom is sixty-six this year and my course is

heavily populated with retirees and eventual retirees seeking to establish new

careers in retirement or to return to a passion postponed. Coincidently, this

summer I had half the normal number of registrants allowing me to get more

deeply into conversations with this great cohort during the course.

Part

of my course concerns the professional of curators and my course material includes

quotes from curators of whom I asked the question: “If you could address the

graduating class of Emily Carr, what is the most important think they should

know, in your opinion, from the entirety of your professional experience?” At

the end of one section of my course this summer, a student who really inspired

me asked if we could get together and when we did, she asked me the same

question. Here is what I told her.

Know

exactly what you want from being an artist. Be it money, public awareness (“fame”)

or curatorial respect or all three or degrees of each—know exactly what you

want from your career. To that add talent and that is half of what you need.

The

other half is one of four things: an incredible work ethic, a balanced and

appreciated extroverted personality, significant business acumen (an

entrepreneurial orientation) or genius. Talent + one of these four qualities =

success no matter how you define it.

Labels:

Art Education,

artrep,

Business Management,

Classroom

Monday, July 23, 2012

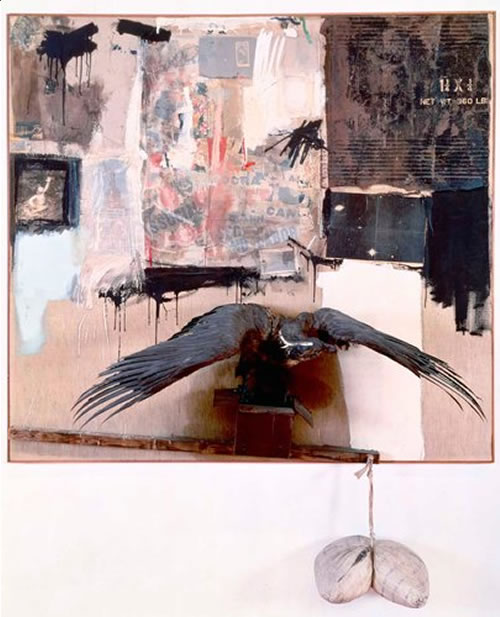

Worth Nothing or $65 Million?

Because the work, a sculptural combine, includes a stuffed bald eagle, a bird under federal protection, the heirs would be committing a felony if they ever tried to sell it. So their appraisers have valued the work at zero.Link

But the Internal Revenue Service takes a different view. It has appraised “Canyon” at $65 million and is demanding that the owners pay $29.2 million in taxes.

“It’s hard for me to see how this could be valued this way because it’s illegal to sell it,” said Patti S. Spencer, a lawyer who specializes in trusts and estates but has no role in the case.

Wednesday, July 11, 2012

Culture Crawl Registration Open

Registration is now open to participate as the 11th annual BC Cultural Crawl, taking place in communities across the province August 1 through 31.

The BC Cultural Crawl provides a vehicle for arts, cultural, heritage and tourism organizations within a community to work together. The results are more strongly integrated communities with tourism and cultural sectors working in tandem.

Register your community, organization or event today.

For helpful tips and hints, view the online toolkit and click here for the FAQ sheet.

The City of Richmond Public Art Program seeks an artist or artist team to create a public artwork to accompany the construction of the Riverport Flats development at 14000 Riverport Way, in close proximity to the Fraser River and to Riverport Sports and Entertainment Complex. This is an open call. See information.

Labels:

Call for Proposals,

Grants,

Public Art

Tuesday, June 26, 2012

Don't Be An Artist

Do you, or have you ever, called yourself

“an artist?” This title, which I once coveted, is now anathema to me.

I remember when I was young wanting so very

badly to be able to say legitimately that I was an artist because I thought it

was the supreme profession. Nothing, I thought, could fill me with greater

pride than to be an artist. But things started happening to me to deter my

ambition early in my education.

My problem was academics. I was reasonably

good at them—particularly with sciences—and so everyone around me, my teachers,

family and friends, encouraged my academic advancement. A practical benefit of

my academic success was scholarships that served to make my post-secondary

education affordable, but they also forced me into an academic track

increasingly focused on the sciences.

As an undergraduate college student,

academic success seemed to create increasing limitations. The more I succeeded,

the narrower my world seemed to become. I found myself in smaller classes,

exposed to fewer students and my courses became more and more focused on biology.

The trouble for me was that my success was unfulfilling.

Academic success seemed to me, as an

undergrad, to be involved with nothing more than memorization and

regurgitation. The quantification of learning into marks and the pressure of

the competitive academic hierarchy created an unwelcome atmosphere; I craved

the ambiguity and freedom of the creative courses that had disappeared from my

life as a scholar. I wanted to be “an artist.”

My discontent was my secret. Everyone

around me was so pleased with what I was doing I felt that I could not express

my frustration. But at the end of my third year at college, I was forced to

declare my dissatisfaction: I turned down an opportunity to be semi

fast-tracked into a pre-med program. For the first time, out loud, I said I

wanted to become an artist. The effect was as though I had said I wanted to

become a cannibal.

Anyone can memorize, I thought. Anyone that

had academic potential, it seemed to me at the time, could be a doctor or a

lawyer if they were prepared to work hard, but being creative seemed to me to

be about the nurturing of a “gift.” Learning could enhance creativity, I

thought, but it could not be academically induced. I craved the opportunity to

test myself in a creative environment instead of academics—creative success, I

knew, would fulfill me.

Now, a career later, I teach business

skills to artists at Emily Carr University and every term, in every class, I

can be heard saying: “Do NOT be an artist.” (I love using what I call “the

provocative tense” when I teach.)

So how have I come to abhor the title that

once so inspired me? The answer is simple. The word “artist” has no meaning as

a professional identifier. It is an insulting answer because it tells the asker

nothing.

Research says the majority of sales by local

contemporary artists are to people with whom the artist has a relationship, so

visual artists with aspirations must make the absolute most of every single

opportunity to establish or to further a relationship, and the question, “What

do you do” affords visual artists with the opportunity to do just that. But if

you answer, “I am an artist,” what is the listener to conclude? You are a

dancer? A writer? An actor?

A person who is truly interested in you, a

person who may become a customer, a fan or a word-of-mouth advertiser for you,

learns nothing from the statement, “I am an artist;” the person is forced to

ask, “What kind of artist?” Even the term, “visual artist” is lacking in enough

specificity. The question, “What do you do?” is an opportunity that you should

maximize. Your answer to this question should be a thoughtful and carefully

crafted one.

The better answer is one that helps the

asker learn more precisely about what you do. I am not advocating that you

respond with a virtual advertisement or that you bore your interlocutor with

too much information. What I advocate is that all visual artists have a

thoughtful, meaningful answer. Consider, for example, these responses:

- I am a (master) printmaker

- I am a creative self-employed professional

- I am a watercolour landscape artist

- I am an artist that, according to the Leadington Star, is a “national treasure”

- I am a wildlife photographer with a fine artist sensibility

- I am a contemporary impressionist

- I am a fine art painter and I teach technique

All these responses to the question, “What

do you do,” are from my students after they have discussed the importance of a

life-long professional identity. Every one of these examples is from a visual

artist who, prior to our discussion, self-identified as simply “an artist.”

The issue here, is your professional

identity; your “brand.” What you call yourself is a vital business decision

worthy of thoughtful reflection. Your professional identity should help people

understand exactly what you do. If you say, simply, that you are “an artist,”

you are throwing away an opportunity.

Every time you introduce yourself to an

individual, to a group, to a jury, a curator, a customer or a potential

customer you have an opportunity to impress and to inform and you should use

it. My advice is to not identify yourself as “an artist,” but instead, to think

of a self-descriptor that is more meaningful and engaging. Reward the person

who expresses interest in you with a thoughtful answer.

Labels:

Marketing,

Nomenclature,

Publicity,

Sales

Saturday, June 2, 2012

Always Interesting: John Baldessari

Join Me: Metchosin Summer School

I am excited

to be part of the Metchosin International Summer School of the Arts this year

at Pearson College. This summer festival of learning and networking expects

over four hundred artists to attend the forty-five workshops on offer. My

workshop is on July 7th and it is a long one: 10:00 am to 3:00 pm.

If you or an artist you know wants an intensive career boost, please let them

know about this opportunity.

Summer Art Fairs

An email from

Betty C. asks: “My gallery sales are down and I’ve been wondering about doing

something I have never wanted to do: participate in a local art ‘festival’ for

lack of a better word. It is part sale, part summer fair, and I have always

thought these kind of events were inappropriate for me. But I need to increase

my sales. Any tips about what to expect or how to maximize my experience?”

After decades of teaching, blogging and

writing about the business of the visual arts, I am lucky to have a very large

mailing list that is now an excellent resource for me. The artists on my list

provide me with rich insights into many aspects of a visual arts career that

are outside my experience. In response to forwarding Bettys’ email, within

twenty-four hours I received a lot of tips:

- Keep a 3-ring binder of images of your other work—sold and unsold. I have gotten commissions for images this way. Also, people like to look through it.

- Keep your table or booth really simple and clean. Keep back-up inventory in your car and get it when you need it. Too much looks messy, uninviting and unprofessional.

- Don’t be afraid of stock piling work. I had a nice clean, professional-looking table at a fair last year, but the guy beside me recently sold his work like crazy, unframed and unmated off a table.

- I use a Digital Photo frame on my table. It features a slide show of most of my work.

- I get far greater interest in my booth if I am working while I am at the fair/sale. People ask me questions and stay longer and often that can lead to a sale. Besides, I am more comfortable painting than just standing there watching them and making them feel uncomfortable.

- I just read about “square.” It's a system that lets you accept credit cards with your smart phone. (http://www.squareup.com)

- A fellow painter told me to leave a couple of spaces empty to make it look like I had sales and apparently it makes people think they should “buy now.” Instead, I decided to put a “sold” sticker on a couple of pieces and then someone came up to me and asked, “Do you have another one like that sold one?” I didn’t know what to do!

- Have LOTS of promotional material ready - with your website on everything and hand it to everyone who will take it. Set up an easel and at least look as though you’re creating. Be ready with your stories...the longer folks are engaged and looking at your work the more likely they'll buy.

- Have an extra folding stool (or two) for a person to use while deciding which of several paintings to buy and be ready to rearrange things so they can focus on those paintings.

- Smile CONSTANTLY even if you haven't sold a single thing; you can never know which visitor might go home and contact you later!

- This year I am teaming up with two other artists with whom I get along and who are using very different styles or media. We can give each other break and we are better at promoting each other than ourselves.

- Be prepared to be tough with organizers. I got a lousy location assigned to me and I was resentful given that I registered early and paid the same fee as everyone else. I asked how I came to be where I was and did not like the explanation. I HATED being a [expletive deleted], but it got me a better location. And thank goodness I was there early enough to become aware of the problem in time to fix it.

- Try not to respond to any compliment by saying, “Thank you”. It ends the conversation. Instead, ask them a question or lead them into a discussion you think they might enjoy. Don’t say, ”Thank you,” until they leave or buy.

- A note about proper behavior at these events. My biggest gripe is often other artists. When I am at an event like this, I am there to sell, not talk to other artists. When other artists engage me, I give them my card and ask them to contact me later because I want to catch the eye, mind and ears of my customers.

- (This was forwarded to me from an unidentified blog.) “I go with my husband and young daughter, we’re a small family and don’t always have a sitter for her. We work together, setting up, taking down and established a rule that only one person at a time in the booth and no eating inside the booth.”

- Sometimes people ask you the dumbest questions imaginable. You have to remember to always take the high road with every response. I often reply simply and politely, and then ask if its their first time at an art fair and if I can answer any questions they might have about choosing art. That may not lead to a sale, but I get them on my mailing list and who knows what will happen down the line.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)